DISCLAIMER: This article does not constitute advice to buy or sell any specific security. You should do your own research and exercise caution when dealing in securities.

Tat Seng Packaging Group Ltd (SGX: T12) designs, manufactures, and sells corrugated packaging solutions to other businesses. This includes corrugated boards, corrugated cartons, die-cut boxes, assembly cartons and heavy-duty corrugated packaging products (see Tat Seng’s website here). In short, they make and sell cardboard packaging to other businesses.

I love simple business models centered on a core product and this fits the bill. I first invested in Tat Seng in mid-2019 (before the Covid-19 pandemic hit) and the shares are already up more than 50% currently. Instead of thinking of selling, I am in fact considering buying more shares.

Company background

Tat Seng was first started in 1968 as ‘Tat Seng Paper Box Maker’. In 1997, Tat Seng expanded to Suzhou in China. Tat Seng listed on the mainboard of the Singapore Exchange in 2001.

In 2005, Hanwell Holdings Limited became the major shareholder of Tat Seng. Hanwell is a company focused on Fast-Moving Consumer Goods, and owns a few well-known brands including Royal Umbrella rice and Beautex tissue products. It also distributes brands such as Mentos, Chupa Chups, Tao Kae Noi, and Indomie in Malaysia. Today, Hanwell owns 64.0% of Tat Seng.

Tat Seng has operations in Singapore, Suzhou, Nantong Rugao, Nantong Tongzhou, Hefei, and Tianjin serving a variety of Multi-National Corporations as well as local businesses.

Industry

I first thought about investing in a packaging company when I was studying in the UK. I saw how uni students were ordering just about everything (stationery, books, electronic devices, bedroom linen, etc.) on Amazon and they were being delivered in disposable packaging. Every evening, our uni hall of residence would receive multiple Amazon deliveries from bike couriers as well as minivans.

Back in 2019, CNBC also released this video which investigated the business of Amazon’s shipping boxes. It illustrated the growth that America’s biggest cardboard box companies were enjoying due to the rapid rise in e-commerce.

With the more recent rise in e-commerce in Asia, we have already seen a flurry of interest in the logistics sector. I do think that the disposable packaging industry is experiencing tailwinds. If anything, Covid-19 pandemic has increased the usage of disposable packaging (for hygiene purposes).

While environmental issues increasingly influencing consumers’ and firms’ decisions, I would not be so quick to assume that this will be the slow death of cardboard packaging. Anecdotally, environmental consciousness appears to me to target single-use plastics a lot more than cardboard. In fact, I have had many experiences with F&B outlets swapping out plastic straws for cardboard ones. While plastic is made from oil (non-renewable resource) and is difficult to recycle, cardboard is made from plant matter (renewable resource) and is already widely recycled. For instance, most companies (I am not sure about Tat Seng) use recycled pulp for the flute (the wavy inner sheet of corrugated cardboard).

Numbers

To me, the profitability of a business can be broken into two separate questions:

- How much product can the business make and sell?

- How much profit can the business earn from the product?

The first question can be answered by looking at revenue. Revenue is the amount of money that the business’ customers hand over. To be profitable, a business must have a product that its customers (whether other businesses or consumers) want and are willing to pay for.

The second question can be answered by looking at margins. There are various ways to calculate margin using different measures of ‘profit’. A margin percentage basically tells us how much of revenue goes into the business owner’s pocket.

Let us take a look at Tat Seng’s numbers from 2013 to 2020. All data presented was extracted from Tat Seng’s annual reports.

Cash flows

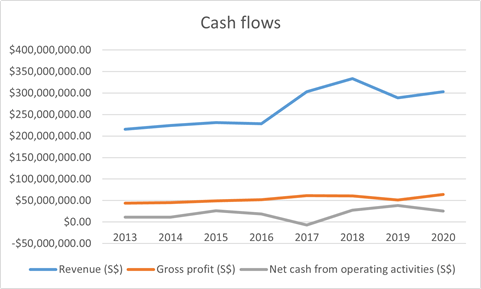

First, revenue, gross profit, and net cash generated (from operating activities).

Over the past 7 years, Tat Seng’s revenue has grown at a CAGR (compound annual growth rate) of about 4.99%. This indicates resilient demand for Tat Seng’s products.

Gross profit (which is calculated as revenue minus cost of production) has been growing at CAGR of about 5.63% over the last 7 years. This is quite impressive, given that the Covid-19 pandemic hit the profitability of many companies around the world quite badly.

We can then calculate gross profit and net cash margins, as shown below.

Margins

The gross profit margin has remained relatively stable at about 20%, which is a good thing. A business that is able to maintain its gross profit margin shows that it has some economic moat such that competitors are unable (or unwilling) to muscle their way into the industry. This is slightly puzzling to me, since cardboard seems to me to be relatively devoid of unique selling points or brand loyalty. I can think of two underlying reasons for this maintained profitability.

First, it could be that Tat Seng has skills, knowledge, or machinery that is able to produce cardboard packaging at a lower cost than other companies. Being the only cardboard company listed on the Singapore Exchange, it is not straightforward to find comparisons, but I might do this in the future against cardboard companies listed in other markets.

Second, it could be that Tat Seng, over its long operating history, has formed close relationships with its customers. This is certainly quite plausible, since the mix of industries it serves has been relatively stable over the years.

| Industry sector | Sales |

| Printing, Publishers & Converters | 45% |

| Medical Health Care, Pharmaceutical & Chemical | 25% |

| Electronics & Electrical | 17% |

| Food & Beverage | 6% |

| Others | 7% |

The table above shows the distribution of sales across industry sectors of its customers, as of FY2020. This looks to me to be a decent mix, and also assures us that Tat Seng is not completely beholden to one or two main customers.

Going back to Chart 2 above, net cash from operating activities and net cash margin briefly became negative in 2017. I took a detailed look at the financial statements during that period and found that this can be explained by trade and other receivables jumping from S$99 million in FY2016 to S$133 million in FY2017. This implies that even though revenue and gross profit increased from 2016 to 2017, customers did not pay Tat Seng immediately, but instead owed it as short-term debt. Looking at the growth in cash pile over the years (see chart below), I think this was a temporary blip rather than a major business problem.

Financial position

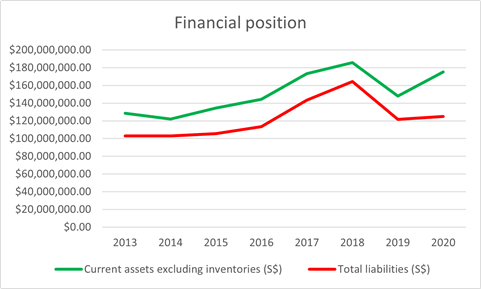

Moving on to balance sheet, which is something I always look at in businesses. A weak balance sheet not only makes the investment very risky, but is also indicative of management that lacks prudence and financial discipline.

For Tat Seng, I am willing to compare current assets excluding inventories (which is cash and cash equivalents plus trade and other receivables) against total liabilities instead of only looking at cash and cash equivalents, because most of Tat Seng’s total liabilities is made up of trade and other payables. I will not, however, consider inventories because I strongly feel that they are a world away from cash in the bank.

Looking at the chart, we can see that Tat Seng has been net cash (if one includes receivables) in the past 7 years, and the financial position is improved sharply in the past one year. In fact, this translates to net current assets of $0.321 per share, which is more than 41% of the current share price.

Overall, Tat Seng’s numbers do look pretty good.

Recent developments

Two recent developments are worth noting.

First, on 25 February 2021, Tat Seng announced that it was exploring the possibility of spinning off and listing of its business operations in China. This announcement sent Tat Seng’s shares flying, from $0.64 on 24 February to $0.81 on 29 March. (You can read the announcement here.)

The China segment is Tat Seng’s main business segment, making up 84.84% of FY2020 revenue. In contrast, the Singapore segment constituted just 15.16% of FY2020 revenue. In my opinion, whether or not this deal (if it even materialises) is good for shareholders will depend heavily on the valuation that Tat Seng gets for its Chinese business operations. I will be looking out for this.

Second, on 29 April 2021, Sam Goi was voted as chairperson of Hanwell Holdings, Tat Seng’s majority shareholder. The previous chairperson of Hanwell, Allan Yap, was declared bankrupt in Hong Kong recently (Allan Yap was also previously the chairperson of Tat Seng, but no longer). Sam Goi is a Singaporean billionaire known for his food manufacturing company, Tee Yih Jia, which is the world’s largest maker of popiah skins (earning him the nickname ‘Popiah King’). Sam Goi, who currently controls 22.67 percent of Hanwell, is expected to attempt to become Hanwell’s executive chairperson. He has also brought a few allies onto the board of Hanwell. While he definitely has plans for Hanwell, it remains to be seen if he will play a direct role in managing Tat Seng. If he does, it may open a new era for Tat Seng. (You can read about Hanwell’s recent boardroom battle here.)

Valuation

Back in 2019 when I first invested in Tat Seng at an average entry price of $0.504, I valued the business conservatively at about $0.60 per share. Today, taking Sam Goi’s recent shake-up of the board of Hanwell into consideration, I would value Tat Seng at $1.40 per share.

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | |

| Net cash from operating activities (S$ million) | 27.7 | 38.4 | 25.8 |

Here is a conservative valuation process. Looking at the net cash generated from operations from the last 3 years, it would be safe to assume that Tat Seng can generate net cash of at least S$20 million in the next few years. Divided by the number of shares outstanding (which is 157,200,000), this gives an estimated minimum future annual net cash of $0.127 per share. At an extremely (in fact, unnecessarily) conservative 8x multiplier, this gives a lower bound on the valuation of Tat Seng shares at $1.016. This still offers a decent margin of safety from the current share price.

My trades

These are my previous trades in shares of Tat Seng (SGX: T12):

- 22 July 2019: BUY at $0.515.

- 5 August 2019: BUY at $0.495.

Today, shares in Tat Seng last traded at $0.77. I am on the lookout for short-term dips in the share price to increase my holdings.

Don’t want to miss out on any articles? SUBSCRIBE with your email address here: