Many Singaporeans (embarrassingly, at times including myself) seem to think of dividends as ‘free money’. You own a stock, and as its owner, you get a reward for investing in the company in the form of dividends. But what exactly are dividends? Are they free money? Should we make investment decisions on the basis of dividend yields? This article will discuss these questions and explain related concepts including dividend reinvestment plans and share buy-backs.

What are dividends?

Dividends are regular payments made by companies to their shareholders from profits earned in the preceding time period. Most companies listed on the Singapore Stock Exchange pay out dividends. They may pay out dividends anywhere from one to four times a year. For example, DBS (SGX: D05) pays out quarterly dividends four times a year, whereas Yangzijiang Shipbuilding Holdings (SGX: BS6) pays out an annual dividend once a year.

I have attached a screengrab below showing Yangzijiang Shipbuilding Holdings’ page on Yahoo finance. You can see the dividend ($0.04 per share per year) and dividend yield (3.04% per year) highlighted in yellow. Dividend yield is the annual dividend amount divided by the share price. (‘Forward’ indicates that this dividend amount and corresponding yield are values projected for the coming year, instead of past data.)

‘Free money’?

So, are dividends really ‘free money’? To answer this question, we will give a simple illustration.

Consider the American Biscuit Company (ABC), which has 100 shares outstanding (that means that each share is ownership of 1% of the company). If ABC shares are trading at $10.00 each on the stock market, this means that investors value ABC at $1,000.

Now consider the financial position of ABC. Assume that ABC has no debt (zero liabilities), and $500 in cash. This $500 has been accumulated over the past few years from profits from selling biscuits. We can therefore infer that investors value ABC’s business excluding cash at $500 ($1,000-$500), since they value the whole company at $1,000 including $500 of cash (surely $1 in cash has value $1).

Out of $10.00 per share, you are essentially paying only $5.00 for the business (including the biscuit factory, brand loyalty, etc.), as you are getting the other $5.00 back in the form of the cash reserves.

Suppose that the boss of ABC decides that due to a large profit the year before, they would like to give a dividend totaling $100 to the shareholders (from ABC’s cash pile of $500). The distribution amount of $1.00 per share will be paid out on 3 June 2021 (known as the payment date) to all those who are who hold ABC shares as of 5pm on 1 June 2021 (known as the ex-date).

| Distribution amount ($ per share) | 1.00 |

| Ex-date | 1 June 2021 |

| Payment date | 3 June 2021 |

This means that after 5pm on 1 June 2021, when ABC makes the legal promise to pay the shareholders then $1.00 per share, ABC’s cash reserves fall by a total of $100 to $400 (or $4.00 per share) as the $100 is set aside to be paid out to shareholders. We can calculate the per-share values (assuming no change in ABC’s underlying business) in the table below.

| Before 5pm, 1 June 2021 | After 5pm, 1 June 2021 |

| One share worth of value of ABC’s business (excluding cash reserves): $5.00 | One share worth of value of ABC’s business (excluding cash reserves): $5.00 |

| One share worth of value of ABC’s cash reserves: $5.00 | One share worth of value of ABC’s cash reserves: $4.00 |

| Cash received from one share: $0.00 | Cash dividend to be received from one share: $1.00 |

| Total value of one share to you $10.00 | Total value of one share to you $10.00 |

So, what is really going on? Well essentially, ABC is handing you a dollar that you had already owned (since your claim of ownership over a part of the company includes a proportional claim over the company’s cash). You get handed $1.00 in cash, but the share price falls by exactly that amount ($1.00) because the company has less cash. You are virtually exactly as well-off as you were before.

To simplify the example further, suppose that you are thinking of buying a second-hand wallet online for $10. The seller then offers to sweeten the deal by leaving a $2-note in the wallet. Surely you would say, why not just sell the wallet to you at a discounted price of $8? This is the exact same reasoning.

True enough, research has shown that share prices tend to drop by approximately the dividend amount on the ex-date, so shareholders are neither better nor worse off due to the distribution. You can read, for instance, this short article by Barker (1959).

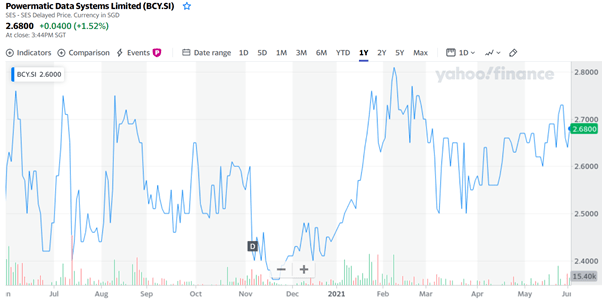

As a specific real-life example, let us take a look at Powermatic Data Systems Limited (SGX: BCY), a stock which I am currently analysing. Last year, Powermatic gave a dividend of 28.6 cents per share (more than 10% of the share price) with ex-date on 5 November 2020 and pay date on 17 November 2020. As you can see from the chart below, the share price plunged on 5 November 2020 by just about 28.6 cents (look for the black square with the ‘D’).

Dividend reinvestment plans

It is common knowledge that in order to reap the full benefits of compounding, investors should reinvest their dividends. Dividend reinvestment plans allow investors to do just that. Dividend reinvestment plans (DRP), also known as scrip dividend schemes, are optional schemes whereby investors can opt to receive their dividends in additional units instead of cash. The new shares are usually issued at a slight discount to the recent trading price.

Why might companies want to offer this? This allows companies to retain their earnings for future investments, while still satisfying those investors who want the cash flow from dividends. If you think about it, if all shareholders opted to participate in the DRP, then each shareholder would just have the exact same proportion of ownership of the company and the company would have exactly as much cash as before the dividend exercise (having not paid out any dividends), so nothing would have changed.

Here is an example of OCBC’s (SGX: O39) recent notice informing shareholders about its DRP.

Share buybacks

Apart from dividends, companies can also return cash to investors through share buy-backs. In gist, a company can buy back its own shares on the market and these shares can either be retired (i.e. ‘deleted’) or kept as treasury shares for future issuance (usually for employee benefits).

Let us go back to the earlier example of the Amazing Biscuit Company. Instead of paying out $100 in dividends ($1.00 to each of the 100 shares), ABC can use the $100 to buy-back 10 shares on the market (since ABC shares are trading at $10.00 each). For convenience, assume that ABC retires those 10 shares, so the number of shares left outstanding is 90.

| Before stock buy-back | After stock buy-back (at market price $10.00) |

| Value of business excluding cash: $500 | Value of business excluding cash: $500 |

| Cash reserves: $500 | Cash reserves: $400 |

| Total value of company including cash: $1,000 | Total value of company including cash: $900 |

| Shares outstanding: 100 | Shares outstanding: 90 |

| Value per share: $10.00 | Value per share: $10.00 |

We can see that if the stock buy-back is done at fair value, it will not affect the value of each share to shareholders. Then why would companies bother with share buy-backs? This is because share prices are constantly fluctuating. Companies tend to buy-back shares when they find the market share price undervalued.

We can adjust the above example by supposing that the market price temporarily dips to $5.00, without affecting the real underlying value of the business. Now, ABC’s $100 can buy-back 20 shares instead of 10, resulting in just 80 shares outstanding after the buy-back.

| Before stock buy-back | After stock buy-back (at market price $5.00) |

| Value of business excluding cash: $500 | Value of business excluding cash: $500 |

| Cash reserves: $500 | Cash reserves: $400 |

| Total value of company including cash: $1,000 | Total value of company including cash: $900 |

| Shares outstanding: 100 | Shares outstanding: 80 |

| Value per share: $10.00 | Value per share: $11.25 |

We can see that if ABC can buy-back stock at a low market price, this can increase the value per share for shareholders. A different way to think about this is to ignore the fact that the company is buying back its own shares, and just think of it as buying undervalued shares. We know that buying shares at a market price lower than intrinsic value is a reliable way to generate healthy returns. If a company notices that its share price is lower than its intrinsic value (based on the company’s management’s judgement), and the company buys its own shares, then it is making a good investment from a value investing point of view.

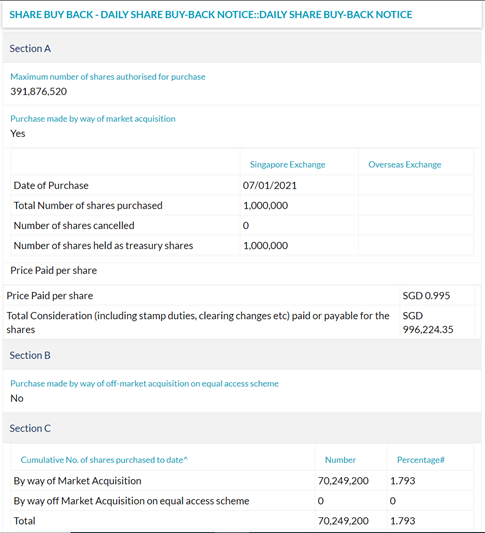

One company that does stock buy-backs well is Yangzijiang Shipbuilding Holdings Limited (SGX: BS6). Yangzijiang usually buys back stock when the share price is around $1 or lower. Below is an example of a share buy-back notice from Yangzijiang on 7 January 2021.

By buying back shares when the market price undervalues the business, Yangzijiang boosts the value of each share for shareholders by increasing their percentage ownership of the business without them needing to cough up any cash.

So, what really matters?

Thus far, we have seen that companies can do a number of things with their earnings, including:

- Investing in new production capacity.

- Investing in research and development.

- Holding cash and waiting for attractive investment opportunities.

- Paying out dividends.

- Buying back shares.

Any of the above might be a good thing. Or a bad thing.

Singapore Press Holdings (SGX: T39) is a company known and loved for its steady dividends. However, it has in recent years been paying out more than it can afford to. You can see that from the chart that between 2016 to 2019, SPH had been paying out more than 100% of operating profit as dividends. That means that it has simply been running down its cash pile. This cannot continue indefinitely, and true enough, SPH cut its dividends drastically in 2020.

The SPH example serves to remind us that companies offering seemingly high and consistent dividends are not necessarily good investments. As every finance website will warn you, past performance is no guarantee of future results.

What really matters are the underlying earnings, which depend on the business model of the company. With respect to dividends, what you should really be concerned with is how earnings are utilized. One famous company that does not pay out dividends is Berkshire Hathaway, the conglomerate led by Warren Buffett. Berkshire seeks large and growing dividends from its investments (such as Apple, Coca Cola, Bank of America, etc.), but does not pay out any dividends to its own shareholders. Berkshire instead uses the cash to invest in existing businesses or for acquisitions. In Warren Buffett’s 2012 annual letter to shareholders, available here, he explained that by retaining earnings, Berkshire puts the earnings to better use than investors otherwise could. If investors would like a stream of cash flow, investors could sell off a small portion of Berkshire shares each year. Berkshire Hathaway also engages in aggressive share buy-backs when the stock is trading lower than Buffett’s calculation of Berkshire’s intrinsic value.

To sum up

- Dividends can be useful as a source of cash for further investing.

- However, what really matters overall is that the profits from a company are being put to good use.

- Focus more on the company’s fundamentals (business model, cash flows, etc.) rather than its dividend yield.